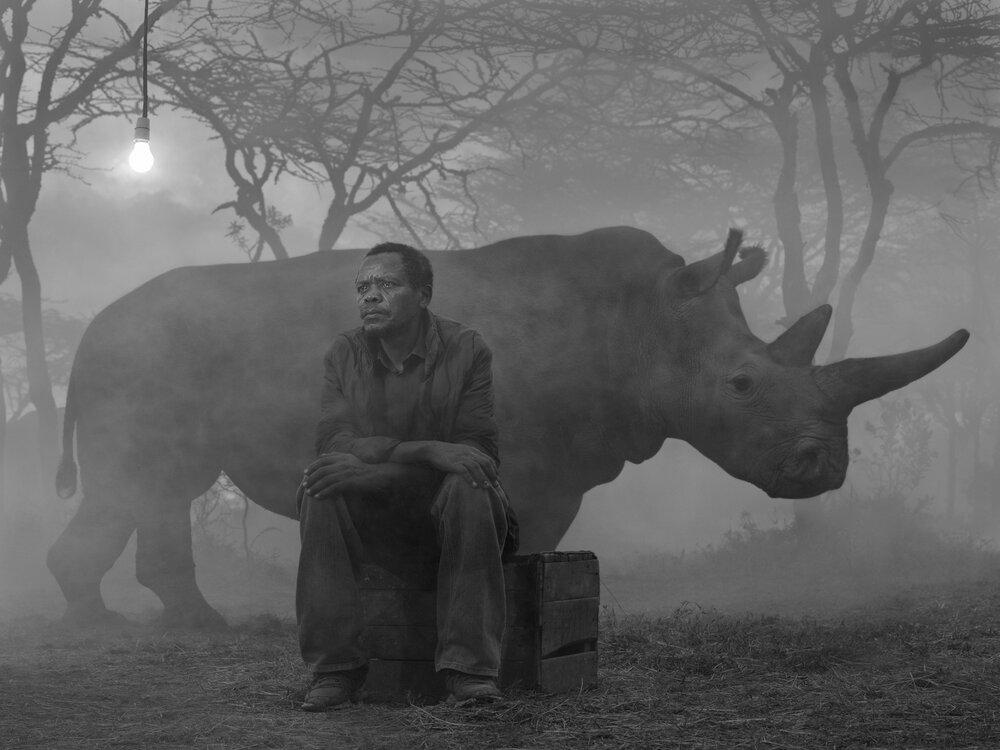

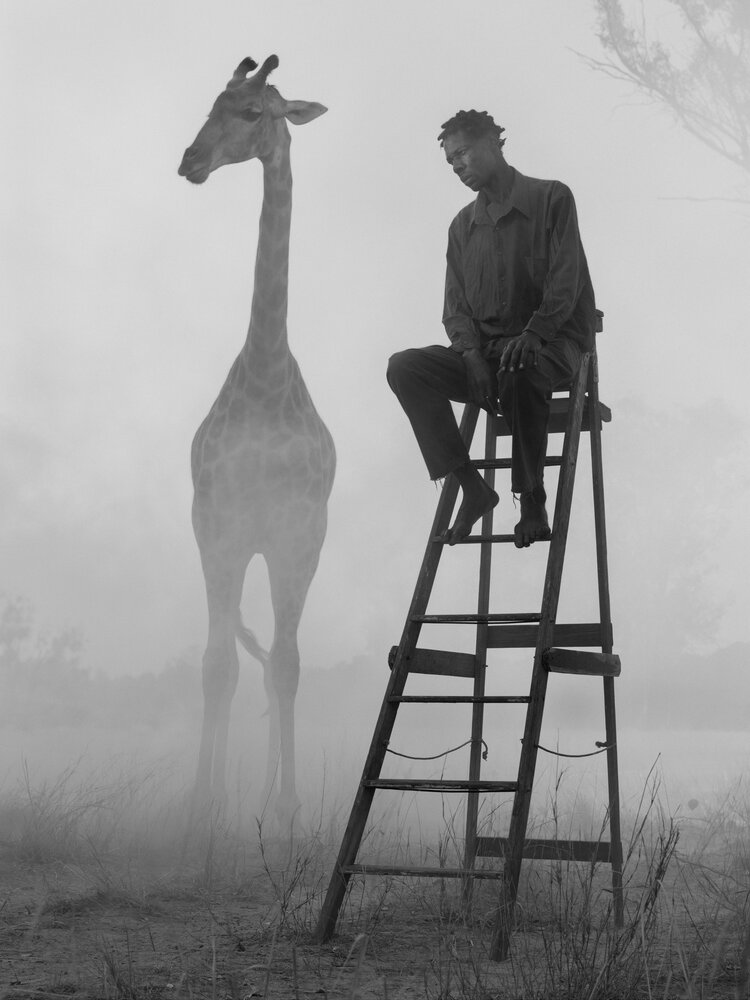

The powerful, mostly monochrome images have people sitting for portraits with a foggy background and rescued animals entering the scene. It looks as if they’re posing together, but the message is that the human characters are victims of environmental degradation and climate change.

Halima, Abdul and Frida, Kenya 2020. Photographed at Ol Jogi Wildlife Conservancy. Frida is a rescued greater kudu. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

Climate change, and its resulting erratic weather patterns, has made Laikipia in central Kenya a flashpoint with clashes between pastoralists, land owners and security organs. 2017 was the bloodiest year, with dozens of lives lost and property destroyed.

This year was similar, with the heavily armed pastoralists invading Laikipia with thousands of cattle in tow. This came after a prolonged drought. The army had to be called in to restore order. Although a century-old land question is one of the reasons touted for the clashes, it’s worrying that every time there’s a drought, conflict sparks up and gets bloodier with each cycle.

SOFIA, HER FATHER MOHAMED & FATU, KENYA, 2020, photographed together in the same frame. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“Photographed at five sanctuaries and conservancies in Kenya and Zimbabwe, including Laikipia’s Ol Pejeta and Ol Jogi, the animals were rescued after poaching incidents, habitat destruction or poisoning,” says Nick Brandt. “They can never be re-introduced to the wild. So it was safe for human strangers to be close to them, photographed in the same frame at the same time.

REGINA, JACK, LEVI AND DIESEL, ZIMBABAWE, 2020, photographed together in the same frame. Source Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“Fog – emanating from fog machines on location – is the unifying visual in the work, as we increasingly find ourselves in a kind of limbo, a natural world we once knew now fading from view. However, in spite of their loss, these people and animals are the survivors. And therein lies possibility and hope,” says Nick Brandt.

The victims, both humans and animals, are photographed together in this fog, in the same frame, because, as Nick says, “We are all denizens of the same home: our actually very small and much endangered planet. We are connected in this time of unprecedented crisis.”

Making of The Day May Break, people and animals always shot together in the same frame at the same time. Zimbabwe. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“I had the concept before COVID, and was going to begin the project in California with wildfire victims and rescued animals there. However, it became logistically impractical during 2020 to shoot there, so I looked further afield. By the time I was ready to photograph, Kenya was open, and so was Zimbabwe. My intention is to attempt California and also South America this coming spring.

HARRIET AND PEOPLE IN FOG, ZIMBABWE, 2020, photographed in the same frame as people. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“It took quite a few months of prep, especially in terms of researching for people whose lives had been impacted by climate change. For Kenya, we were able to focus around the Nanyuki area. Many people there have lost hope of a continued farming existence. They’ve lost their homes due to years of severe droughts, and in a few instances, extreme floods,” says the veteran photographer.

The shoot itself took two months, three weeks in Kenya and five weeks in Zimbabwe. The crew was around 10-12 people, most of whom were operating the non-toxic water-based fog machines. One cannot fail to notice the blank looks on the faces of the characters. Was it a theme to show uncertainty of the future, fear or past trauma?

James and Fatu, Kenya 2020. Fatu is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“I tried to direct as little as possible. With some people it worked best looking straight into the camera. Helen, Lene and Shyline, Fatuma and Ali, Robert and Nyaguthii, Sofia, Alice – and others it worked best when they were looking away like Teresa, Luckness, Richard, James, Jack and Regina, Patrick, Kuda. There wasn’t a conscious overview taken of the whole. Only that I wanted the girls to be the strongest. But that came naturally, and I just followed,” explains Nick.

Did he face any challenges while photographing the animals and people in close proximity? “Not the animals, who were incredibly cooperative. Nor the people, who were all calm, gracious and patient working with these animals in such close proximity to them. Again, the people and animals were all photographed together in the same frame at the same time.

RICHARD AND SKY, ZIMBABWE, 2020, photographed together. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break.

“It was the weather that was the biggest challenge. Not so much in Kenya where it was mercifully cool and quite damp most days, but in Zimbabwe, where we had three weeks of extreme heat and sunny blue skies, low humidity and bone-dry winds. In those instances, the fog evaporated immediately and we really only had thirty minutes before sunrise and thirty minutes after sunset in which to photograph,” explains Nick Brandt.

Nick co-founded Big Life Foundation in 2010 with Richard Bonham. Back then, their main priority was poaching. They tackled it by forming a large number of anti-poaching units across the ecosystem and a good informant network.

Fatuma, Ali & Bupa, Kenya, 2020, photographed together, from the new series, The Day May Break. Source | Nick Brandt.

The next problem was human-wildlife conflict, which again was largely dealt with by the Big Life Foundation raising funds to build over 100km of fence separating farms from wildlife habitat and a successful livestock compensation scheme. Now the biggest problem of all is land subdivision. The Foundation is rapidly raising funds to lease critical wildlife corridors as other areas get fenced and developed.

“I think there absolutely is hope for co-existence,” Nick says. “Although each area has its own set of specific challenges. But by supporting the local communities – a holistic but also very pragmatic approach where local communities clearly economically benefit from conservation – then yes. But I think we all already know that in 21st century Africa, that really is the only way forward. And it’s the right way ethically too.”

Photographed in Zimbabwe and Kenya in late 2020, it is the first part of a global series portraying people and animals impacted by environmental degradation and destruction. Source | Nick Brandt: The Day May Break

His previous books ‘Inherit the Dust’ and ‘This Empty World’ had a lot of terrifying truths, were haunting and almost apocalyptic, in my opinion, but The Day May Break seems to be a hopeful narrative and a story of survival.

“Actually, I think that this new work, The Day May Break, is less apocalyptic. There was no apparent hope present in the last two series (Inherit the Dust and This Empty World). In this work, the point is all the subjects in the photos are survivors. These people have been through such hardships – their livelihoods, their homes destroyed, and in a few instances even their children drowned in floods – but they are still here. Same for the animals.

“As the title’s dual interpretation hopefully intimates: The Day May Break, and the world may shatter. Or The Day May Break, and a new dawn comes with it. Humanity’s choice. Our choice. However, I do think we have gone beyond the tipping point with climate breakdown. It’s now a case of trying to mitigate the damage, which we can do, and still save billions of lives in the process,” says Nick Brandt.

New Series / Exhibitions / Book released on Sept 8 : The Day May Break https://www.nickbrandt.com/